Hemophilia can result in:

- Joint swelling that can lead to damage or swelling in the muscle

- Bleeding in the head and sometimes in the brain leading to brain damage

- Damage to other organs in the body

- Pain as a result of bleeding in various organs

- Death can occur if the bleeding cannot be stopped or if it occurs in a vital organ such as the brain.

Statistics

- Hemophilia affects 1 in 5,000 male births. About 400 babies are born with hemophilia each year.

- The exact number of people living with hemophilia in the United States is not known. A CDC study conducted in six states in 1994 estimated that about 17,000 people had hemophilia at that time. Currently, the number of people with hemophilia in the United States is estimated to be about 20,000, based on expected births and deaths since 1994.

|

"Do the 5" Tips for Healthy Living

1. Get an annual comprehensive checkup at a hemophilia treatment center.

TypesThere are several different types of hemophilia. The following two are the most common:

|

Signs and Symptoms

The major signs of hemophilia are bleeding that is unusually heavy or lasts a long time, or bleeding and bruising that happens without obvious cause. The amount of bleeding depends on the type and severity of hemophilia and how serious it is.

Other common signs include:

- Bleeding into the joints. This can cause swelling and pain or tightness in the joints; it often affects the knees, elbows, and ankles.

- Bleeding into the skin (which is bruising) or muscle and soft tissue causing a build-up of blood in the area (called a hematoma).

- Bleeding of the mouth and gums, and bleeding that is hard to stop after losing a tooth.

- Bleeding after circumcision (surgery performed on male babies to remove the hood of skin, called the foreskin, covering the head of the penis).

- Bleeding after having shots.

- Bleeding in the head of an infant after a difficult delivery.

- Blood in the urine or stool.

- Frequent and hard-to-stop nosebleeds.

Causes

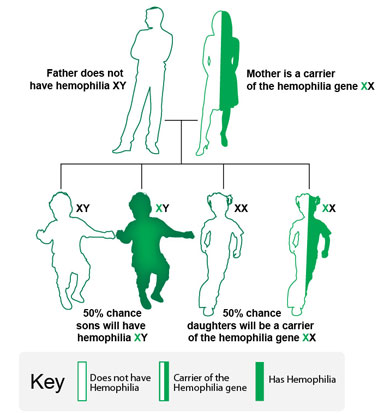

Hemophilia is caused by a problem in one of the genes that tells the body to make the clotting factor proteins needed to form a blood clot. These genes are located on the X chromosome. All males have one X and one Y chromosome (XY) and all females have two X chromosomes (XX).Males who inherit an affected X chromosome have hemophilia. Rarely, a condition called "female hemophilia" occurs. In such cases both X chromosomes are affected or one is missing or inactive. In these women, bleeding symptoms may be similar to males with hemophilia.

A female who inherits one affected X chromosome becomes a "carrier" of hemophilia. A female who is a carrier sometimes can have symptoms of hemophilia. In addition, she can pass the affected gene on to her children.

Even though hemophilia is genetic, it does occur among families with no prior history. About one-third of newly diagnosed babies have no family history of hemophilia. These cases are thought to be due to a change to the gene's instructions for making the clotting factor protein, called a "mutation." This change or mutation can prevent the clotting protein from working properly or to be missing altogether.

Understanding Hemophilia (Home Use) DVD

How Hemophilia is Inherited

The following examples show how the hemophilia gene can be inherited. It is important to note that in one-third of people with hemophilia, there is no family history of the disorder.1. In this example, the mother is a carrier of the hemophilia gene, and the father does not have hemophilia.

- There is a 50% chance that each son will have hemophilia.

- There is a 50% chance that each daughter will be a carrier of the hemophilia gene.

2. In this example, the father has hemophilia, and the mother does not carry the hemophilia gene.

- All daughters will carry the hemophilia gene.

- No sons will have hemophilia.

3. In this example, the father does not have hemophilia, and the mother does not carry the hemophilia gene.

- None of the children (daughters or sons) will have hemophilia or carry the gene.

Who is Affected

Hemophilia is a common inherited bleeding disorder. Hemophilia occurs among about 1 of every 5,000 male births. Currently, about 20,000 males in the United States have the disorder. Hemophilia A is about four times as common as hemophilia B, and about half of those affected have the severe form. Hemophilia affects people from all racial and ethnic groups.Diagnosis

Textbook of Hemophilia

|

Many people who have or have had family members with hemophilia will ask that their baby boys get tested soon after birth.

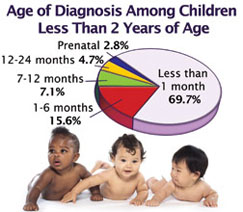

In the United States, most people with hemophilia are diagnosed at a very young age. Based on CDC data, the median age at diagnosis is 36 months for people with mild hemophilia, 8 months for those with moderate hemophilia, and 1 month for those with severe hemophilia. About one-third of babies who are diagnosed with hemophilia have no other family members with the disorder. A doctor might check for hemophilia if a newborn is showing certain signs of hemophilia. Diagnosis includes screening tests and clotting factor tests. Screening tests are blood tests that show if the blood is clotting properly. Clotting factor tests, also called factor assays, are required to diagnose a bleeding disorder. This blood test shows the type of hemophilia and the severity. |

Families With a History of Hemophilia

Any family history of bleeding, such as following surgery or injury, or unexplained deaths among brothers, sisters, or other male relatives such as maternal uncles, grandfathers, or cousins should be discussed with a doctor to see if hemophilia was a cause. A doctor often will get a thorough family history to find out if a bleeding disorder exists in the family.

Many people who have or have had family members with hemophilia will ask that their baby boys get tested soon after birth. In the best of cases, testing for hemophilia is planned before the baby’s delivery so that a sample of blood can be drawn from the umbilical cord (which connects the mother and baby before birth) immediately after birth and tested to determine the level of the clotting factors. Umbilical cord blood testing is better at finding low levels of factor VIII (8) than it is at finding low levels of factor IX (9). This is because factor IX (9) levels take more time to develop and are not at a normal level until a baby is at least 6 months of age. Therefore, a mildly low level of factor IX (9) at birth does not necessarily mean that the baby has hemophilia B. A repeat test when the baby is older might be needed in some cases. Learn more about the inheritance pattern for hemophilia.

Families With No Previous History of Hemophilia

About one-third of babies who are diagnosed with hemophilia have no other family members with the disorder. A doctor might check for hemophilia in a newborn if:

- Bleeding after circumcision of the penis goes on for a long time.

- Bleeding goes on for a long time after drawing blood and heel sticks (pricking the infant’s heel to draw blood for newborn screening tests).

- Bleeding in the head (scalp or brain) after a difficult delivery or after using special devices or instruments to help deliver the baby (e.g., vacuum or forceps).

-

Those with severe hemophilia can have serious bleeding problems right away. Thus, they often are diagnosed during the first year of life. People with milder forms of hemophilia might not be diagnosed until later in life.

Screening Tests

Screening tests are blood tests that show if the blood is clotting properly. Types of screening tests:

Complete Blood Count (CBC)

This common test measures the amount of hemoglobin (the red pigment inside red blood cells that carries oxygen), the size and number of red blood cells and numbers of different types of white blood cells and platelets found in blood. The CBC is normal in people with hemophilia. However, if a person with hemophilia has unusually heavy bleeding or bleeds for a long time, the hemoglobin and the red blood cell count can be low.

Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT) Test

This test measures how long it takes for blood to clot. It measures the clotting ability of factors VIII (8), IX (9), XI (11), and XII (12). If any of these clotting factors are too low, it takes longer than normal for the blood to clot. The results of this test will show a longer clotting time among people with hemophilia A or B.

Prothrombin Time (PT) Test

This test also measures the time it takes for blood to clot. It measures primarily the clotting ability of factors I (1), II (2), V (5), VII (7), and X (10). If any of these factors are too low, it takes longer than normal for the blood to clot. The results of this test will be normal among most people with hemophilia A and B.

Fibrinogen Test

This test also helps doctors assess a patient’s ability to form a blood clot. This test is ordered either along with other blood clotting tests or when a patient has an abnormal PTExternal Web Site Icon or APTT testExternal Web Site Icon result, or both. Fibrinogen is another name for clotting factor I.

Clotting Factor Tests

Clotting factor tests, also called factor assays, are required to diagnose a bleeding disorder. This blood test shows the type of hemophilia and the severity. It is important to know the type and severity in order to create the best treatment plan.

Severity Levels of Factor VIII (8) or IX (9) in the blood Normal (person who does not have hemophilia) 50% to 100% Mild hemophilia Greater than 5% but less than 50% Moderate hemophilia 1% to 5% Severe hemophilia Less than 1% Treatment

Hemophilia is a complex disorder. Good quality medical care from doctors and nurses who know a lot about the disorder can help prevent some serious problems. Often the best choice is a comprehensive Hemophilia Treatment Center (HTC). An HTC provides care to address all issues related to the disorder, as well as education.- A CDC-sponsored randomized clinical trial found that children who were treated on a regular basis to prevent bleeding had less evidence of joint damage by 6 years of age than did those who were treated only after a bleed had started.

- About 70% of people with hemophilia in the United States receive multidisciplinary, comprehensive care in a network of federally funded hemophilia treatment centers.

- Mortality rates and hospitalization rates for bleeding complications from hemophilia were 40% lower among people who received care in hemophilia treatment centers than among those who did not receive this care.

The best way to treat hemophilia is to replace the missing blood clotting factor so that the blood can clot properly. This is done by injecting commercially prepared clotting factor concentrates into a person’s vein. The two main types of clotting factor concentrates available are:

Plasma-Derived Factor Concentrates

Plasma is the liquid part of blood. It is pale yellow or straw colored and contains proteins such as antibodies, albumin and clotting factors. Several factor concentrates that are made from human plasma proteins are available. All blood and parts of blood, such as plasma, are routinely tested for the viruses. The clotting proteins are separated from other parts of the plasma, purified, and made into a freeze-dried product. This product is tested and treated to kill any potential viruses before it is packaged for use. A blood safety surveillance system in place since 1998 has found no new infections with hepatitis or HIV associated with these products among hemophilia patients.

Recombinant Factor Concentrates

Until 1992, all factor replacement products were made from human plasma. In 1992, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved recombinant factor VIII (8) concentrate, which does not come from human plasma. The concentrate is genetically engineered using DNA technology. Commercially prepared factor concentrates are treated to remove or inactivate bloodborne viruses. In addition, recombinant factors VIII (8) and IX (9) are available that do not contain any plasma or albumin and, therefore, cannot transmit any bloodborne viruses.

The products can be used as needed when a person is bleeding or they can be used on a regular basis to prevent bleeds from occurring. Today, people with hemophilia and their families can learn how to give their own clotting factor at home. Giving factor at home means that bleeds can be treated quicker, resulting in less serious bleeding and fewer side effects.

Other treatment products:

DDAVP® (Desmopressin Acetate)

DDAVP® is a chemical that is similar to a hormone that occurs naturally in the body. It releases factor VIII (8) from where it is stored in the body tissues. For people with mild, and some cases of moderate hemophilia, this can work to increase their own factor VIII (8) levels so that they do not have to use clotting factor. This medicine can be given through a vein (DDAVP®) or through nasal spray (Stimate®).

Amicar® (Epsilon Amino Caproic Acid)

Amicar® is a chemical that can be given in a vein or by mouth (as a pill or a liquid). It prevents clots from breaking down, resulting in a firmer clot. It is often used for bleeding in the mouth or after a tooth has been removed because it blocks an enzyme in the saliva that breaks down clots.

Cryoprecipitate

Cryoprecipitate is a substance that comes from thawing fresh frozen plasma. It is rich in factor VIII (8) and was commonly used to control serious bleeding in the past. However, because there is no method to kill viruses, such as HIV and hepatitis, in cryoprecipitate it is no longer used as the current standard of treatment in the U.S. It is, however, still used in most developing countries.

Inhibitors

About 10 – 15 percent of people with hemophilia develop an antibody (called an inhibitor) that inhibits the action of the clotting factors used to treat bleeding. Treatment of bleeding becomes extremely difficult, and the cost of their care can skyrocket because more clotting factor or a different type of clotting factor is needed. Patients with inhibitors often experience increased joint disease and other complications from bleeding that result in a reduced quality of life.

About InhibitorsPeople with hemophilia use treatment products called factor clotting concentrates. This treatment improves blood clotting and is used to stop or prevent a bleeding episode. Inhibitors develop when the body’s immune system stops accepting the factor (factor VIII for hemophilia A and factor IX for hemophilia B) as a normal part of blood. The body thinks the factor is a foreign substance and tries to destroy it using inhibitors. The inhibitors stop the factor from working. This makes it more difficult to stop a bleeding episode. People with hemophilia who develop an inhibitor do not respond as well to treatment. Inhibitors most often appear during the first year of treatment but they can appear at any time.

Cost of Care

Caring for people with inhibitors poses a special challenge. The health care costs associated with inhibitors can be staggering because of the cost and amount of treatment product required to stop bleeding.1 Also, people with hemophilia who develop an inhibitor are twice as likely to be hospitalized for a bleeding complication.2

Risk Factors and Causes

Scientists do not know exactly what causes inhibitors. Risk factors that have been shown in some studies to possibly play a role include:

- Age

- Race/ethnicity

- Type of hemophilia gene defect

- Frequency and amount of treatment (inhibitors typically occur within the first 50 times factor is used)

- Family history of inhibitors

- Type of factor treatment product

- Presence of other immune disorders

Diagnosis

A blood test is used to diagnose inhibitors. The blood test measures inhibitor levels (called inhibitor titers) in the blood. The amount of inhibitor titers is measured in Bethesda units (BU). The higher the number of Bethesda units, the more inhibitor is present. “Low titer” inhibitor has a very low measurement, usually less than 5 BU. “High titer” inhibitor has a very high measurement, usually much higher than 5 BU.

Inhibitors are also labeled “low responding” or “high responding” based on how strongly a person’s immune system reacts or responds to repeated exposure to factor concentrate. When people with high-responding inhibitors receive factor concentrates, the inhibitor titer measurement increases quickly. The increased inhibitor titer prevents the factor clotting concentrates from stopping or preventing a bleeding episode. Repeated exposure to factor clotting concentrates will cause more inhibitors to develop.

When people with low-responding inhibitors receive factor concentrates, the inhibitor titers do not rise. Therefore, people with low-responding inhibitors can usually still use factor clotting concentrates to stop or prevent a bleeding episode.

Treatment

Treating people who have inhibitors is complex and remains one of the biggest challenges in hemophilia care today. If possible, a person with inhibitors should be cared for at a hemophilia treatment center (HTC). HTCs are specialized health care centers that bring together a team of doctors, nurses, and other health professionals experienced in treating people with hemophilia.

Woman doctor in scrubsSome treatments for people with inhibitors include the following:

- High-Dose Clotting Factor Concentrates: People who have low responding inhibitors may be treated with higher amounts of factor concentrate to overcome the inhibitor and yet have enough left over to form a clot. It is important to test the blood and measure the factor level after this new treatment schedule is established to see if the inhibitor is gone.

- Bypassing Agents: Special blood products are used to treat bleeding in people with high titer inhibitors. They are called bypassing agents. Instead of replacing the missing factor, they go around (or bypass) the factors that are blocked by the inhibitor to help the body form a normal clot. People taking bypassing agents should be monitored closely to make sure the blood is not clotting too much or clotting in the wrong place in the body.

- Immune Tolerance Induction (ITI) Therapy: The goal of ITI therapy is to stop the inhibitor reaction from happening in the blood and to teach the body to accept clotting factor concentrate treatments. With ITI therapy, people receive large amounts of clotting factor concentrates every day for many weeks or months.

ITI therapy requires specialized medical expertise, is costly, and may take a long time to work. In many cases, ITI gets rid of the inhibitor. However, patients may need to continue taking frequent, large amounts of factor concentrates for many years to keep the inhibitor from coming back. HTCs can serve a vital role in supporting patients who undergo a treatment regimen as intensive as ITI.

Did You Know?

When people are being treated for an inhibitor, they receive frequent, large amounts of clotting factor concentrates and therefore may need a central venous access device (CVAD). A CVAD is a small tube placed in a vein. It can stay in the vein for a long time. Clotting factor concentrates can be given through the CVAD instead of by injection or infusion through a painful needle stick. A downside of having a CVAD is that people with CVADs are more likely to develop infections, blood clots, and other complications than those without CVADs. It is important for people with hemophilia and their caregivers to learn how to care for the device.

CDC Research

CDC is interested in learning more about why some people develop inhibitors and how they could be prevented. The Inhibitor Project began in 2005 and was implemented to explore the following questions:

- Does a change in treatment products (from one type of factor product to another) lead to an inhibitor?

- Are people with specific gene mutations more likely to develop an inhibitor?

- What characteristics make some people more likely to develop an inhibitor than others?

- Why do some people develop inhibitors and others do not?

- How often do inhibitors occur?

In the Inhibitor Project, a limited number of federally funded hemophilia treatment centers across the United States enroll study participants who have hemophilia A or hemophilia B. Detailed information about their hemophilia, their complications, and their treatment is collected and studied over time. The CDC laboratory tests each participant’s blood and determines if he or she has an inhibitor. Testing all of the blood at the CDC laboratory, rather than using several different labs throughout the country, ensures that the testing procedures are consistent and reliable for analysis. The blood samples are also used to study hemophilia-related genes and gene mutations to learn more about who is more likely to develop an inhibitor even before treatment is started. The laboratory results are shared with the study participant’s physician.

Through additional research, we hope to increase our understanding of inhibitors. Knowing more about why some people develop inhibitors and others do not may help us predict who will develop an inhibitor before treatment is started. This may lead to a decreased rate of inhibitors, decreased health care costs, and the licensure of safe and more effective treatment products for people with hemophilia.

More Information

Hemophilia (Genes and Disease)National Hemophilia Foundation

World Federation of Hemophilia Adobe PDF file