What is giardiasis?

Giardiasis is a diarrheal illness caused by a microscopic parasite called Giardia intestinalis (also known as Giardia lamblia or Giardia duodenalis). A parasite is an organism that feeds off of another to survive. The parasite is found on surfaces or in soil, food, or water that has been contaminated with feces (poop) from infected humans or animals. People can become infected after accidentally swallowing the Giardia parasite. Once a person or animal (for example, cats, dogs, cattle, deer, and beavers) has been infected with Giardia, the parasite lives in the intestines and is passed in feces (poop). Once outside the body, Giardia can sometimes survive for weeks or months. Giardia can be found within every region of the U.S. and around the world.Giardiasis is a global disease. It infects nearly 2% of adults and 6% to 8% of children in developed countries worldwide. Nearly 33% of people in developing countries have had giardiasis. In the United States, Giardia infection is the most common intestinal parasitic disease affecting humans.

Electron micrograph of Giardia trophozoite. |

G. intestinalis trophozoites in a Giemsa stained mucosal imprint. Photo credit: DPDx, CDC |

How do you get giardiasis and how is it spread?

People become infected with Giardia by swallowing Giardia cysts (hard shells containing Giardia) found in contaminated food or water. Cysts are instantly infectious once they leave the host through feces (poop). An infected person might shed 1-10 billion cysts daily in their feces (poop) and this might last for several months. However, swallowing as few as 10 cysts might cause someone to become ill. Giardia may be passed person-to-person or even animal-to-person. Also, oral-anal contact during sex has been known to cause infection. Symptoms of giardiasis normally begin 1 to 2 weeks (average 7 days) after a person has been infected.

|

Giardia infection rates have been known to go up in late summer. Between 2006-2008 in the United States, known cases of giardiasis

were twice as high between June-October as they were between January-March.

Giardiasis can be spread by:

Anything that comes into contact with feces (poop) from infected humans or animals can become contaminated with the Giardia parasite. People become infected when they swallow the parasite. It is not possible to become infected through contact with blood. |

Image: Left: G. intestinalis trophozoites in Kohn stain.

Center: G. intestinalis cyst stained with trichrome.

Right: G. intestinalis in in vitro culture, from a quality control slide. Credit: DPDx

Biology

Giardia intestinalis is a protozoan flagellate (Diplomonadida). This protozoan was initially named Cercomonas intestinalis by Lambl in 1859. It was renamed Giardia lamblia by Stiles in 1915 in honor of Professor A. Giard of Paris and Dr. F. Lambl of Prague. However, many consider the name, Giardia intestinalis, to be the correct name for this protozoan. The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature is reviewing this issue.

Life Cycle:

|

Cysts are resistant forms and are responsible for transmission of giardiasis. Both cysts and trophozoites can be found in the feces

(diagnostic stages)

The number 1. The cysts are hardy and can survive several months in cold water. Infection occurs by the ingestion of cysts in contaminated water, food, or by the fecal-oral route (hands or fomites) The number 2. In the small intestine, excystation releases trophozoites (each cyst produces two trophozoites) The number 3. Trophozoites multiply by longitudinal binary fission, remaining in the lumen of the proximal small bowel where they can be free or attached to the mucosa by a ventral sucking disk The number 4. Encystation occurs as the parasites transit toward the colon. The cyst is the stage found most commonly in nondiarrheal feces The number 5. Because the cysts are infectious when passed in the stool or shortly afterward, person-to-person transmission is possible. While animals are infected with Giardia, their importance as a reservoir is unclear. |

What are the symptoms of giardiasis?

Giardia infection can cause a variety of intestinal symptoms, which include:

- Diarrhea

- Gas or flatulence

- Greasy stool that can float

- Stomach or abdominal cramps

- Upset stomach or nausea

- Dehydration

These symptoms may also lead to weight loss. Some people with Giardia infection have no symptoms at all.

Other, less common symptoms include itchy skin, hives, and swelling of the eye and joints. Sometimes, the symptoms of giardiasis might seem to resolve, only to come back again after several days or weeks. Giardiasis can cause weight loss and failure to absorb fat, lactose, vitamin A and vitamin B12.

In children, severe giardiasis might delay physical and mental growth, slow development, and cause malnutrition.

How long after infection do symptoms appear?

Symptoms of giardiasis normally begin 1 to 2 weeks (average 7 days) after becoming infected.

How long will symptoms last?

In otherwise healthy people, symptoms of giardiasis may last 2 to 6 weeks. Occasionally, symptoms last longer. Medications can help decrease the amount of time symptoms last. Who is most at risk of getting giardiasis?Though giardiasis is commonly thought of as a camping or backpacking-related disease and is sometimes called "Beaver Fever," anyone can get giardiasis. People more likely to become infected include: Image of kids playing and coloring at a day care.

Children in child care settings, especially diaper-aged children are at risk for Giardia exposure.

- Children in child care settings, especially diaper-aged children

- Close contacts (for example, people living in the same household) or people who care for those sick with giardiasis

- People who drink water or use ice made from places where Giardia may live (for example, untreated or improperly treated water from lakes, streams, or wells)

- Backpackers, hikers, and campers who drink unsafe water or who do not practice good hygiene (for example, proper handwashing)

- People who swallow water while swimming and playing in recreational water where Giardia may live, especially in lakes, rivers, springs, ponds, and streams

- International travelers

- People exposed to human feces (poop) through sexual contact

What should I do if I think I may have giardiasis?

Contact your health care provider.New Guinea Tapeworms and Jewish Grandmothers: Tales of Parasites and People

Giardia and Giardiasis: Biology, Pathogenesis, and Epidemiology

How is a giardiasis diagnosed?Your health care provider will ask you to submit stool (poop) samples to see if you are infected.Because Giardia cysts can be excreted intermittently, multiple stool collections (i.e., three stool specimens collected every other day) increase test sensitivity. The use of concentration methods and trichrome staining might not be sufficient to identify Giardia because variability in the concentration of organisms in the stool can make this infection difficult to diagnose. For this reason, fecal immunoassays that are more sensitive and specific should be used. Rapid immune-chromatographic cartridge assays also are available but should not take the place of routine ova and parasite examination. Only molecular testing (e.g., polymerase chain reaction) can be used to identify the subtypes of Giardia. |

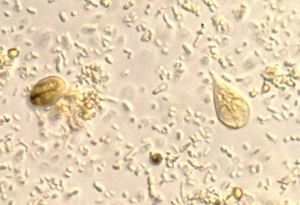

Giardia trophozoites and cysts. Credit: Waterborne Disease Prevention Branch, CDC |

What is the treatment for giardiasis?

Many prescription drugs are available to treat giardiasis. Although the Giardia parasite can infect all people, infants and pregnant women may be more likely to experience dehydration from the diarrhea caused by giardiasis. To prevent dehydration, infants and pregnant women should drink a lot of fluids while ill. Dehydration can be life threatening for infants, so it is especially important that parents talk to their health care providers about treatment options for their infants.Several drugs can be used to treat Giardia infection. Effective treatments include metronidazole, tinidazole, and nitazoxanide. Alternatives to these medications include paromomycin, quinacrine, and furazolidone. Some of these drugs may not be routinely available in the United States.

Different factors may shape how effective a drug regimen will be, including medical history, nutritional status, and condition of the immune system. Therefore, it is important to discuss treatment options with a health care provider.

My child does not have diarrhea, but was recently diagnosed as having Giardia infection. My health care provider says treatment is not necessary. Is this correct?

Your child does not usually need treatment if he or she has no symptoms. However, there are a few exceptions. If your child does not have diarrhea, but does have other symptoms such as nausea or upset stomach, tiredness, weight loss, or a lack of hunger, you and your health care provider may need to think about treatment. The same is true if many family members are ill, or if a family member is pregnant and unable to take the most effective medications to treat Giardia. Contact your health care provider for specific treatment recommendations.

If my water comes from a well, should I have my well water tested?

Where and how does Giardia get into drinking water?

Millions of Giardia parasites can be released in a bowel movement of an infected human or animal. Human or animal waste can enter the water through different ways, including sewage overflows, sewage systems that are not working properly, polluted storm water runoff, and agricultural runoff. Wells may be more vulnerable to such contamination after flooding, particularly if the wells are shallow, have been dug or bored, or have been submerged by floodwater for long periods of time.

How can I find out whether there is Giardia in my drinking water?

If you suspect a problem and your drinking water comes from a private well, you may contact your state certification officer for a list of laboratories in your area that will perform tests on drinking water for a fee.

How can I remove Giardia from my drinking water?

To kill or inactivate Giardia, bring your water to a rolling boil for one minute (at elevations above 6,500 feet, boil for three minutes) Water should then be allowed to cool, stored in a clean sanitized container with a tight cover, and refrigerated.

An alternative to boiling water is using a point-of-use filter. Not all home water filters remove Giardia. Filters that are designed to remove the parasite should have one of the following labels:

- Reverse osmosis,

- Absolute pore size of 1 micron or smaller,

- Tested and certified by NSF Standard 53 for cyst removal, or

- Tested and certified by NSF Standard 53 for cyst reduction.

To learn more, visit CDCís A Guide to Water Filters page.

As you consider ways to disinfect your well, it is important to note that Giardia is moderately chlorine resistant. Contact your local health department for recommended procedures. Remember to have your well water tested regularly, at least once a year, after disinfection to make sure the problem does not recur.

What can I do to Prevent and Control giardiasis?

To prevent and control infection with the Giardia parasite, it is important to:

- Practice good hygiene

- Avoid water (drinking or recreational) that may be contaminated

- Avoid eating food that may be contaminated

- Prevent contact and contamination with feces (poop) during sex

Practice good hygiene

- Everywhere

- Wash hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, cleaning all surfaces well,

even under the nails

- Before preparing or eating food

- After using the bathroom

- After changing diapers or cleaning up a child who has used the toilet

- Before and after tending to someone who is ill with diarrhea

- After handling animals or their toys, leashes, or feces (poop)

- After touching something that could be contaminated (such as a trash can, cleaning cloth, drain, or soil)

- Wash hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, cleaning all surfaces well,

even under the nails

- Help young children and other people you are caring for with handwashing as needed

- At child care facilities

- To reduce the risk of spreading the disease, children with diarrhea should be removed from child care settings until the diarrhea has stopped

- At recreational water venues (for example, pools, beaches, fountains)

- Protect others by not swimming if you have diarrhea (this is most important for children in diapers)

- Shower before entering the water

- Wash children thoroughly (especially their bottoms) with soap and water after they use the bathroom or after their diapers are changed and before they enter the water

- Take children on frequent bathroom breaks and check their diapers often

- Change diapers in the bathroom, not by the water

- Around animals

- Minimize contact with the feces (poop) of all animals, especially young animals

- When cleaning up animal feces (poop), wear disposable gloves and always wash hands when finished

- Minimize contact with the feces (poop) of all animals, especially young animals

- Wash hands after any contact with animals or their living areas

- Outside

- Wash hands after gardening, even if wearing gloves

- Do not swallow water while swimming in pools, hot tubs, interactive fountains, lakes, rivers, springs, ponds, streams or the ocean

- Do not drink untreated water from lakes, rivers, springs, ponds, streams, or shallow wells

- Do not drink poorly treated water or ice made from water during community outbreaks caused by contaminated drinking water

- Do not use or drink poorly treated water or use ice when traveling in countries where the water supply might be unsafe

- If the safety of drinking water is in doubt (for example, during or after an outbreak, in a place with poor

sanitation or lack of water treatment systems), do one of the following:

- Drink bottled water

- Disinfect tap water by heating it to a rolling boil for 1 minute

- Use a filter that has been tested and rated by National Safety Foundation (NSF) Standard 53 or NSF Standard 58 for cyst and oocyst reduction; filtered tap water will need additional treatment to kill or weaken bacteria and viruses

Practicing good hygiene is a great step toward preventing transmission of diseases. |

|

|

Thoroughly washing your hands after gardening can help prevent exposure to parasitic diseases. |

Avoid water (drinking and recreational) that may be contaminated

A Guide to Water Filters

Filtering tap water: Many but not all available home water filters remove Cryptosporidium. Some filter designs are more suitable for removal of Cryptosporidium than others. Filters that have the words "reverse osmosis" on the label protect against Cryptosporidium. Some other types of filters that function by micro-straining also work. Look for a filter that has a pore size of 1 micron or less. This will remove microbes 1 micron or greater in diameter (Cryptosporidium, Giardia). There are two types of these filters ó "absolute 1 micron" filters and "nominal 1 micron" filters but not all filters that are supposed to remove objects 1 micron or larger from water are the same. The absolute 1 micron filter will more consistently remove Cryptosporidium than a nominal filter. Some nominal 1 micron filters will allow 20% to 30% of 1 micron particles (like Cryptosporidium) to pass through.

NSF-International (NSF) does independent testing of filters to determine if they remove Cryptosporidium. To find out if a particular filter is certified to remove Cryptosporidium, you can look for the NSF trademark plus the words "cyst reduction" or "cyst removal" on the product label information. You can also contact the NSF at 789 N. Dixboro Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48113 USA, toll free 800-673-8010 or 888-99-SAFER, fax 734-769-0109, email info@nsf.org, or visit their Web site. At their Web site, you can enter the model number of the unit you intend to buy to see if it is on their certified list, or you can look under the section entitled "Reduction claims for drinking water treatment units - Health Effects" and check the box in front of the words "Cyst Reduction." This will display a list of filters tested for their ability to remove Cryptosporidium.

Because NSF testing is expensive and voluntary, some filters that may work against Cryptosporidium have not been NSF-tested. If you chose to use a product not NSF-certified, select those technologies more likely to reduce Cryptosporidium, including filters with reverse osmosis and those that have an absolute pore size of 1 micron or smaller.

Package and Label Information for Purchasing Water Filters

Filters designed to remove Crypto (any of the four messages below on a package label indicate that the filter should be able to remove Crypto)

- Reverse osmosis (with or without NSF testing)

- Absolute pore size of 1 micron or smaller (with or without NSF testing)

- Tested and certified by NSF Standard 53 or NSF Standard 58 for cyst removal

- Tested and certified by NSF Standard 53 or NSF Standard 58 for cyst reduction

Filters labeled only with these words may NOT be designed to remove Crypto

- Nominal pore size of 1 micron or smaller

- One micron filter

- Effective against Giardia

- Effective against parasites

- Carbon filter

- Water purifier

- EPA approved Caution: EPA does not approve or test filters

- EPA registered Caution: EPA does not register filters based on their ability to remove Cryptosporidium

- Activated carbon

- Removes chlorine

- Ultraviolet light

- Pentiodide resins

- Water softener

- Chlorinated

Note:

Filters collect germs from water, so someone who is not immunocompromised should change the filter cartridges. Anyone changing the cartridges should wear gloves and wash hands afterwards. Filters may not remove Cryptosporidium as well as boiling does because even good brands of filters may sometimes have manufacturing flaws that allow small numbers of Cryptosporidium to get in past the filter. Selection of NSF-Certified filters provides additional assurance against such flaws. Also, poor filter maintenance or failure to replace the filter cartridges as recommended by the manufacturer can cause a filter to fail.

A Guide to Commercially-Bottled Water and Other Beverages

If you drink commercially-bottled water, read the label and look for this information.

Commercially-Bottled Drinking Water Labeling Information

Water so labeled has been processed by a method effective against Crypto

- Reverse osmosis treated

- Distilled

- Filtered through an absolute 1 micron or smaller filter

- "One micron absolute"

Water so labeled MAY NOT have been processed by a method effective against Crypto

- Filtered

- Micro-filtered

- Carbon-filtered

- Particle-filtered

- Multimedia-filtered

- Ozonated

- Ozone-treated

- Ultraviolet light-treated

- Activated carbon-treated

- Carbon dioxide-treated

- Ion exchange-treated

- Deionized

- Purified

- Chlorinated

Commercially-bottled water labels reading "well water," "artesian well water," "spring water," or "mineral water" do not guarantee that the water does not contain Crypto. However, commercially-bottled water that comes from protected wells or protected springs is less likely to contain Crypto than water from less protected sources, such as rivers and lakes. Any bottled water (no matter what the source) that has been treated by one or more of the methods listed in the left column in the table above should be safe.

Other Beverages

Soft drinks and other beverages may or may not contain Cryptosporidium (Crypto) parasites. You need to know how they were prepared to know if they might contain Crypto.

If you drink prepared drinks, look for drinks prepared in a manner that removes Crypto:

Prepared Beverages and Crypto Risk

Drinks that ARE safe

- Carbonated (bubbly) drinks in cans or bottles

- Commercially-prepared fruit drinks in cans or bottles

- Steaming hot (175 degrees F or hotter) tea or coffee

- Pasteurized drinks

Drinks that may NOT be safe

- Fountain drinks

- Fruit drinks you mix with tap water from frozen concentrate

- Iced tea or iced coffee

Juices made from fresh fruit can also be contaminated with crypto. For example, an outbreak of cryptosporidiosis occurred in Ohio whereby several people became ill after drinking apple cider made from apples contaminated with Crypto. You may wish to avoid unpasteurized juices or fresh juices if you do not know how they were prepared.

Avoid eating food that may be contaminated

- Use safe, uncontaminated water to wash all food that is to be eaten raw

- After washing vegetables and fruit in safe, uncontaminated water, peel them if you plan to eat them raw

- Avoid eating raw or uncooked foods when traveling in countries with poor food and water treatment

Prevent contact and contamination with feces (poop) during sex

- Use a barrier during oral-anal sex

- Wash hands right after handling a condom used during anal sex and after touching the anus or rectal area