Aging Hearts and Arteries Part I

Click here for Aging Heart and Arteries Part II

Click here for Aging Heart and Arteries Part III

Click here for Aging Heart and Arteries Part IV

The Mission of the National Institute on Aging

"...the conduct and support of biomedical, social and behavioral research, training, health information dissemination, and other programs with respect to the aging process and the diseases and other special problems and needs of the aged."

Research on Aging Act of 1974, as amended in 1990 by P.L. 101-557

|

Introduction

Age is the major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Heart disease and stroke incidence rises steeply after age 65, accounting for more than 40 percent of all deaths among people age 65 to 74 and almost 60 percent at age 85 and above. People age 65 and older are much more likely than younger people to suffer a heart attack, to have a stroke, or to develop coronary heart disease and high blood pressure leading to heart failure. Cardiovascular disease is also a major cause of disability, limiting the activity and eroding the quality of life of millions of older people each year. The cost of these diseases to the Nation is in the billions of dollars.

To understand why aging is so closely linked to cardiovascular disease, and ultimately to understand the causes and develop cures for this group of diseases, it is essential to understand what is happening in the heart and arteries during normal aging—aging in the absence of disease. This understanding has moved forward dramatically in the past 30 years. The purpose of this booklet is to tell the story of this progress, describe some of the most important findings, and give a sense of what may lie ahead.

| | |

While we know a great deal about cardiovascular disease and its risk factors, new areas of research are beginning to shed further light on the link between aging and the development and course of the disease. For instance, scientists at the National Institute on Aging (NIA) are paying special attention to certain age-related changes that occur in the arteries and their influence on cardiac function.Many of these changes, once considered a normal part of aging, may put people at increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

This and other compelling research on the aging heart and blood vessels takes place at many different research centers. A great deal of the work is being done by researchers in the Laboratory of Cardiovascular Science at the NIA or by NIA-funded scientists at other institutions. Others have worked at or been funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). NIA and NHLBI are two of 27 research institutes and centers at the National Institutes of Health, and their work is complementary. NIA research focuses on the effects of aging on the heart, blood vessels, and other parts of the body, while NHLBI works to understand the diseases and risk factors that affect the heart and blood vessels.

Both perspectives are bringing us closer to the possibility that heart disease and stroke will someday be defeated. Research on the basic biology of the aging cardiovascular system nurtures hope that we as a Nation need not accept the high rates of death and disability and the enormous health care costs imposed by cardiovascular disease among older people in our society.

Richard J. Hodes, MD, Director, National Institute on Aging

Chapter 1: A Host of Interconnections

"The heart is purest theater…throbbing in its cage palpably as any nightingale."

Richard Selzer, MD, American Surgeon and Author

It is scarcely as big as the palm of your hand yet it sustains life, pumping up to 5 quarts or more ofblood per minute to the body’s organs, tissues, and cells. In a typical day, it beats 100,000 times. And in a lifetime, it beats more than 2.5 billion times. Even as you rest, your heart is working twice as hard as your leg muscles would if you were running at full speed.

Little wonder then that from earliest mythology to modern medicine, the heart has fascinated and perplexed us. Fortunately, today we know farmore about the heart and the blood vessels than was known even a decade ago. Yet for all scientists have learned, there is still much more to unravel. Investigators, for instance, now know that the cardiovascular system undergoes significant changes as we age, and the heart and arteries that we are born with are surprisingly different in later life.

But how and why do these changes occur? What influence do these changes have on our risk of developing heart disease and other cardiovascular disorders as we get older? Are there any underlying signs—even in people who appear to have healthy hearts—that precede and predict who will develop severe cardiovascular disease and who won’t?

Scientists called gerontologists, who study aging, are seeking to answer these and other questions. As a result of this probing, some old ideas about the aging cardiovascular system are giving way to new theories. In other cases, gerontologists are just beginning to explore some questions, and the heart and arteries are yielding their secrets grudgingly.

But to truly understand what is emerging and what remains mysterious, we’ll need to start where these gerontologists began: in the normal, healthy heart.

|

The Intricate Pump

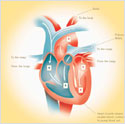

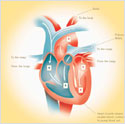

The heart is a marvel of coordination and timing. Almost completely composed of muscle called myocardium, it is well-equipped for its life-long marathon of ceaseless beating. It is essentially two pumps in one. The right side pumps blood to the lungs to load up on oxygen and dispose of carbon dioxide. The left side pumps oxygen-rich blood to the body.

To accomplish these tasks, the heart depends on a precise sequence of contractions involving its two upper chambers—the right and left atria—and its two lower ones, the right and left ventricles. Between these chambers are two valves, each with two or three flaps, also known as cusps. The tricuspid valve separates the right atrium and the right ventricle. Its counterpart, separating the left atrium and the left ventricle, is called the mitral valve. The pulmonic valve controls blood flow out of the right ventricle to the lungs where it picks up oxygen. The aortic valve controls the flow of oxygenated blood out of the left ventricle into the body. Normally these valves let blood flow in just one direction.

| | Anatomy of the Heart

Click here for larger view Click here for larger view |

The heart beats in two synchronized stages. First, the right and left atria contract at the same time pumping blood into the right and left ventricles. Then the mitral and tricuspid valves close. A split second later, the ventricles contract (beat) simultaneously to pump blood out of the heart. Together, these coordinated contractions produce the familiar “lub-dub” sound of a heart beat—slightly faster than once a second.After contracting, the heart muscles momentarily relax, allowing blood to refill the heart.

To picture how this all works, imagine that as the heart relaxes dark red blood returning from the body flows into the right atrium. This blood carries little oxygen and is laden with carbon dioxide, which is produced by body tissues. When the right atrium contracts, it propels oxygen-poor blood through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. In turn, the right ventricle pumps blood into the pulmonary artery. From there, it flows into the lungs where it picks up oxygen and returns to the left atrium. When it contracts, the left atrium pumps the now bright red oxygenated blood through the mitral valve into the left ventricle, which pumps it into the aorta, from which it is distributed to other arteries to nourish your cells, tissues, and organs. Then the cycle begins again.

This cardiac cycle is regulated by nerve impulses, generated by the heart’s internal pacemaker called the sinoatrial node (SA node), a small bundle of specialized cells located in the right atrium. These impulses cause the heart to beat.Once generated by the SA node, the impulses spread in a coordinated fashion across the heart muscle in less than a quarter of a second. As they travel, the impulses are relayed through switching stations at precise intervals, eventually causing millions of interlocked cells to contract in near unison.

Age, Change, and Adaptation

The major sequences in this ever-moving picture of the heart beat have been known for nearly 400 years. But gerontologists are uncovering another influence on this chain of events—age—and the picture appears to be even more complex. Aging, it turns out, brings not a simple slowing down of heart function, as one might expect, but a set of intricate alterations: a slowing here, an enhancement there, a minor adjustment elsewhere. The result of these numerous small alterations is adaptation. In various ingenious, important ways, the heart at age 65 has adapted to meet the needs of the 65-year-old body.

However, these refinements have a downside. In recent years, gerontologists have learned that some changes in the structure and function of the aging cardiovascular system, even in a healthy older person without any diagnosed medical condition, can actually greatly increase the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, including high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, and heart failure. In fact, these changes can create the nearly perfect setting for the onset of severe cardiovascular disease in some healthy older people.

Gerontologists seeking to reconcile these two conflicting pictures of cardiovascular aging are intensely studying the fundamental underpinnings of the age-associated changes in the heartand arteries in hopes of discovering new ways to effectively prevent and treat cardiovascular disease in older people. This quest—from the impact of the smallest molecule to the influence of diet and exercise—is radically changing how scientists think about the cardiovascular system.

The notion, for instance, that heart cells can’t replicate themselves is being reconsidered. Gerontologists now know far more about how aging affects blood vessels and how this process influences the development of atherosclerosis. They are learning much more about how physical activity, diet, and other lifestyle factors influence the “rate of aging” in the healthy older heart and arteries.

|

In the Beginning

Untangling the effects of age from those of disease and lifestyle is a theme that appears again and again in modern studies of aging. It wasn’t always so. In the 1940s and 50s, clinical gerontologists had to conduct most of their studies in chronic care hospitals or nursing homes. The people they studied lived sedentary lives, and many may have had undetected heart disease or other illnesses. From this perspective, it appeared as if virtually all bodily functions, including the cardiovascular system, deteriorated markedly with age.

Then, in 1958, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) launched the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA). This ongoing investigation, now part of the National Institute on Aging (NIA), has tracked the lives of more than 3,000 people from age 20 to 90 and older in an effort to document the normal or usual physiological changes that occur in a stable population of people who live in the community rather than institutions. BLSA data have been valuable to scientists searching for different ways in which aging, lifestyle, and disease affect the heart and blood vessels.

The modern era of heart research has also depended heavily on the development of powerful, non-invasive technologies, such as echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging, and radionuclide imaging, which have allowed investigators to easily see valves, walls, and chambers of the heart and the flow of blood through these chambers. Two techniques, thallium scintigraphy, a highly sensitive radionuclide stress test that can detect hidden coronary artery disease, and stress electrocardiogram (ECG), a measurement of the electrical activity of the heart, are particularly useful. In combination, these two tests allow researchers to differentiate between the effects of age and the effects of coronary disease that is so prevalent among older people—effects that were once entangled and indistinguishable.

The Next Steps

As you explore this booklet, you will find that scientists have learned a tremendous amount about aging. Today, more than ever, they understand what causes your blood vessels and heart to age and know a lot about how this process interacts with cardiovascular disease-related changes. In addition, they have even pinpointed risk factors that increase the odds a person will develop cardiovascular disease as well as other illnesses. And while many mysteries of the aging heart and arteries remain unsolved, gerontologists have discovered much about how to prevent or postpone heart disease in later life.

| | Picture of woodcut from 1523

and MRI from 2005

Scientists have been

fascinated with the heart for

centuries. Left: This 1523

woodcut by Jacopo

Berengario da Carpi was

sophisticated for its time.

Right: Today, researchers

use magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) and other

high-tech tools to study the

living heart. |

Chapter 2: The Aging Heart

|

"The heart is a tough organ: a marvelous mechanism that, mostly without repairs, will give valiant pumping service up to a hundred years."

Willis John Potts, MD, American Surgeon, 1895-1968

For 92-year-old John Bicknell, this is the best of times. A long-retired English professor, he remains mentally and physically active. In addition to singing in community choirs and performing in local musical theater productions, he continues to mow his own large yard and often walks up to a mile or two a day around his island home in Maine.

As he walks around his property, Bicknell sometimes gathers small twigs and branches for kindling, and makes a mental note of larger deadfall so he and his son-in-law can return later to cut it up and haul it back to the house in a truck. An avid boater, he frequently motors between the island and the mainland. In the summer, he enjoys swimming with his grandchildren in the brisk, but invigorating waters of a nearby cove. | Photo of John Bicknell

|

After a recent trip to England and France, he returned home to a brewing winter storm. The next morning, he shoveled 9-inches of snow off his deck and front porch.

He looks healthy; his muscles are strong; he has no excess fat. And while gerontologists now know that John Bicknell’s 92-year-old heart is not quite the same as it was when he was 22, it continues to serve him extraordinarily well.

On one level, it’s not surprising that an older person who exercises regularly is more physically fit and better able to care for himself than most other people his age. But below the surface of that assumption lie intriguing questions that scientists are just beginning to answer. “We know that older people who exercise regularly can do more aerobic work, meaning they are more physically fit,” says Edward Lakatta, MD, who is chief of the Laboratory of Cardiovascular Science at the NIA. “But for decades gerontologists have wanted to know what changes in the aging heart and arteries allow this to happen. Fortunately, in the past few years, we have uncovered some remarkable new clues that have clarified how and why these changes occur. At the same time, however, we have detected some intriguing evidence that transforms much of what we once thought of as normal cardiovascular aging.”

Many of these adjustments are remarkably efficient, helping the older heart work as well as possible. But some ultimately may be detrimental. In particular, some gerontologists suspect several of these age-related changes may lower the heart’s resistance to disease and compromise its ability to respond to increased demands for blood and oxygen during stress.

|

"Fortunately, in the past few years, we have uncovered some remarkable new clues that have clarified how and why these changes occur. At the same time, however, we have detected some intriguing evidence that transforms much of what we once thought of as normal cardiovascular aging."

EDWARD LAKATTA, MD, CHIEF OF THE LABORATORY OF CARDIOVASCULAR SCIENCE, NIA |

The Effects of Normal Aging

The emerging methods of studying the heart have led to the growing realization that the many factors influencing the aging heart and blood vessels are interdependent. At least six major factors affect how the heart fills with blood and pumps it out. When scientists first discovered these factors, they thought they operated independently. But as investigators more closely examined these factors, they discovered that these six factors influence each other in various direct and indirect ways.

The diagram on the facing page illustrating their interdependence is deceptively simple. It shows only the six broad categories, but each of these terms encompasses a host of related factors. Many of these factors are the focus of rigorous research, including structural changes in the normal aging heart.

|

Structural Changes

The NIA’s studies of normal aging have revealed a series of fine-tuned adjustments that allow the heart to meet the needs of the aging body. This picture is radically different from the one that prevailed several decades ago when marked declines in overall heart function were thought to be the norm. The revolution in perspective began in the 1970s when researchers came upon their first surprise: The walls of the left ventricle, as it ages, grow thicker.

Up until then, gerontologists thought that the heart shrank with age. One reason was that early researchers knew about the older heart mainly through chest x-rays and autopsy studies of people who were institutionalized, often with chronic illnesses. These people’s hearts, which were affected by disease or extremely sedentary lives, often were smaller than those of younger, healthier people.

| | Heart Dynamics

Click here for Click here for

larger view |

Then, in the late 1950s, gerontologists began to study healthy volunteers, such as those who participate in the BLSA. Soon afterward, scientists devised new technologies like echocardiography and radionuclide imaging.While x-rays provide a static, shadowy silhouette, echocardiography and other imaging techniques clearly show thickness, diameter, volume, and in some cases, shape of the heart and how these change with time during a given heart beat. Recently, gerontologists have begun using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to get a better look at the aging heart. MRI is a type of body scan that uses magnets and computers to provide high-quality images based on varying characteristics of the body’s tissues. The technology allows physicians to noninvasively study the beating heart’s overall structure and function continuously in three dimensions.

|

The thicker left ventricular walls supplied the first clue that the heart might be adjusting rather than simply declining with age. Scientists think that the increased thickness allows the walls to compensate for the extra stress they bear with age (stress imposed by pumping blood into stiffer blood vessels, for instance). When walls thicken, stress is spread out over a larger area of heart muscle.

Heart Filling

Other findings about the left side of the heart soon followed. While at the NIA, Gary Gerstenblith, MD, and his colleagues studied the left ventricle and the left atrium, the receiving chamber into which blood flows from the lungs before passing into the ventricle. Their echocardiograms with BLSA volunteers showed that in addition to the left ventricular wall growing thicker, the cavity of the left atrium increased.

| |

Gary Gerstenblith, MD |

This study also yielded one other finding, a curious one: The mitral valve—the gateway between the left atrium and ventricle—appeared to close more slowly in older people. As the ventricle fills, the two flaps of the mitral valve—like a trap door with two separate panels—float up on the rising pool of blood and come together to close the passage. If this valve were closing more slowly in older people, as the echocardiograms indicated, then perhaps the ventricle was filling more slowly.

To figure out why this occurs and if it makes any difference, investigators turned their attention to the fraction of a second between heart beats. During this momentary lull, called the diastole, the heart relaxes, fills with blood, and readies for the next contraction or systole.

Heart researchers divide the moments of diastole into even shorter periods. There is the early filling phase when blood from the left atrium pushes the mitral valve open, flows rapidly into the left ventricle, and floats the valve shut. This early diastolic filling is the phase that takes longer as people grow older, according to the Gerstenblith study. Then comes the late filling phase, when the left atrium contracts, forces open the mitral valve a second time, and delivers a last surge of blood to the ventricle, just before it too contracts.

Why should early diastolic filling slow down as people age? Could it be because the ventricle wall was not relaxing between heart beats as quickly as it once had?

|

This possibility intrigued NIA investigators because it fit neatly with another stray piece to the puzzle. In animal studies several years earlier, Dr. Lakatta had learned that rat hearts studied in the laboratory took longer to relax after a contraction when they were from older rats.

Later imaging studies in humans confirmed the animal studies: Between beats, the aging ventricle fills with blood more slowly because it is relaxing more slowly than it did when young.

| | In a Heartbeat

Click here for

larger view |

But now another piece of the diastolic puzzle needed to be fit into place.If the older left ventricle fills more slowly with blood, does this mean it has less blood pooled at the end of diastole and thus less to send out to the body during the next contraction? The answer is no, and the reason was found in another of the adjustments that the heart makes with age. NIA investigators found that the heart compensates for the slower early filling rate by filling more quickly in the late diastolic period.

It happens like this: As the mitral valve slowly closes, incoming blood from the lungs pools in the left atrium, which is now larger and holds more blood than when young. In the last moments of the diastole, the SA node—the heart’s pacemaker—triggers the first electrical impulse (the action potential), which will lead to contraction. The impulse spreads across the cells of the two atria.

The left atrium, stretched with a greater volume of blood in older hearts, contracts harder, pushing open the valves and propelling the blood into the ventricle. The late diastolic surge of blood into the left ventricle from the atrium’s contraction occurs at all ages but is stronger in older hearts and delivers a greater volume of blood to the left ventricle. As a result, at the end of diastole, the volume of blood in older hearts is about the same (in women) or slightly greater (in men) than in younger hearts. In younger people, about twice as much blood flows into the ventricle during the early filling period than during late filling. But as we age, this ratio changes so blood flow during early and late filling is about equal.

The next step in this chain of events is contraction or systole, and here the puzzle becomes more complex.

Picture the left ventricle at the end of diastole filled with a volume of blood that is equal to or slightly greater than the volume in younger hearts; this is called end diastolic volume. When the contraction occurs, it forces out a certain amount of blood—the stroke volume. However, not all of the blood in the heart is pumped out at once. A portion remains in the ventricle, and this is called the end systolic volume. The proportion of blood that is pumped out during each beat compared to the amount that remains in the heart at the beginning of the next beat is called the ejection fraction. Doctors frequently use the ejection fraction to estimate how well the heart is pumping.

These measurements are important because the links between end diastolic volume, stroke volume, end systolic volume, and ejection fraction make up a complex set of dynamics that researchers had to sort out as they attempted to understand what differences aging makes in the heart’s pumping ability. The various cardiac volumes differ according to age, gender, body size and composition, and degree of physical activity. However, keep in mind that the various changes discussed in this section are what occur, on average, in older hearts. As we age, the differences in these measures between one individual and another will vary much more than in younger people. So, for instance, among 65 to 70-year-old women the range of end diastolic volumes and stroke volumes can be quite vast.

|

Pumping at Rest

When you are sitting in a chair reading a book or watching television, your heart—regardless of age—usually works well below its full capacity. Instead, the heart saves or reserves most of its capacity for times when it is really needed, such as playing tennis or shoveling snow.

In fact, at first glance, healthy young and old hearts don’t seem very different—at least when resting. For instance, cardiac output—the amount of blood pumped through the heart each minute—averages 4 to 6 quarts per minute at rest depending on body size and doesn’t change much with age. Similarly,while resting, both young and old hearts eject about two-thirds of the blood in the left ventricle during each heart beat.

But on closer examination, there is at least one important difference between a healthy resting young heart and an older one: heart rate. When we’re lying down, the rates of young and old hearts remain about the same. But when we’re sitting, heart rate is less in older people compared to younger men and women, in part, because of age-associated changes in the sympathetic nervous system’s signals to the heart’s pacemaker. As we age, some of the pathways in this system may develop fibrous tissue and fat deposits. The SA node, the heart’s natural pacemaker, loses some of its cells.

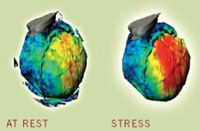

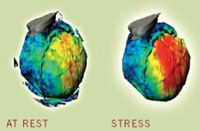

| | Photos of heart in action

at rest and in stress

The heart requires more energy and

more blood during exertion or other

times of stress. These metabolic images dramatically show the difference in blood flow through the heart at rest and during

stress. Red indicates greater blood

flow to that portion of the heart. |

In men, the heart compensates partly for this decline in two ways. First, the increase in end diastolic volume that comes with age, means there is more blood to pump; and second, the greater volume stretches the ventricular walls and brings into play a peculiar property of muscle cells—the more they are stretched, the more they contract. This phenomenon is called the Frank-Starling mechanism and together with the greater volume of blood to be pumped, it helps to make up for the lower heart rate.

In women, end diastolic volume while sitting does not increase with age, so stroke volume does not increase. The difference between the sexes probably reflects their different needs rather than a difference in their hearts’ pumping abilities.

But while the resting older heart can keep pace with its younger counterpart, the older heart—even if in peak condition—is no match for a younger one during exercise or stress.

|

Pumping During Exercise

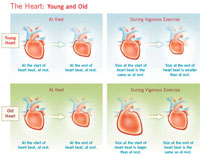

It’s no secret that the ability to run, swim, and exert ourselves in other ways diminishes as we get older. In fact, the body’s capacity to perform vigorous exercise declines by about 50 percent between the ages of 20 and 80. About half of this decline can be attributed to changes in the typical aging heart.

During any kind of activity—even moving from a sitting to a standing position—the heart must pump more blood to the working muscles. In younger people it does this by increasing the heart rate and squeezing harder during contractions, sending more blood with each beat. But age brings changes. Heart rate still rises, but it can no longer rise as high. In your 20s, for instance, your maximum heart rate is typically about 190 to 200 beats per minute; by age 80, this rate has diminished to about 145 beats per minute. A reduced response of heart cells to signals from the brain result in a substantial decline in the peak rate at which the older heart can beat. In addition, force of contraction during vigorous exercise increases, but not as much in older people as in younger ones.

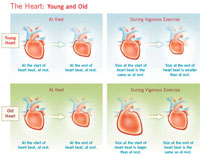

| | The Heart: Young and Old

Click here for

larger view |

As a result, the heart’s cardiovascular reserve diminishes. Put another way, a typical 20-year-old can increase cardiac output during exercise to 31/2-4 times over resting levels. In comparison, by age 80, a person can only muster about two times as much cardiac output as at rest.

Yet the aging heart still must respond to many of the same demands as the younger heart. To do so, it takes advantage of its natural flexibility. The heart, which is composed of elastic-like material, can readily alter shape and size depending on the amount of blood within its chambers.

At rest, only a small portion of the body’s blood supply is flowing into the heart at any given moment. But with exertion, your body sends out signals that increase blood flow from the veins back to the heart initially stretching and swelling it. This triggers the Frank-Starling mechanism. In response, the young heart pumps harder. Then the brain kicks in, releasing neurotransmitters that elevate heart rate, increase contraction strength, and boost ejection fraction. In addition, the young heart returns to its small, resting size at the start of each beat. All of these reactions help the young heart work more efficiently.

|

But the older heart doesn’t respond in the same way. Although the brain still releases neurotransmitters that stimulate the heart to work harder during vigorous exercise, the older heart is less responsive to these signals than the younger heart. And unlike the young heart, it can’t squeeze down to a small size at the end of a heart beat. So its ejection fraction increases only slightly from its resting level of about 65 percent during vigorous exercise. In addition, you might recall that the older heart can’t increase its rate as much as the younger heart during exertion. So if it can’t beat as fast or squeeze down as hard, then how does the older heart respond to the demands of exercise? The answer is: it adapts.

Because its pumping rate increases less during exercise, the older heart has more time than a younger heart to fill with blood between beats. This additional filling time, combined with a lower ejection fraction, causes the older heart to expand to a larger size during diastole than a young heart. As a result, during exercise the older, bigger heart has more blood in its chambers at the start of each beat than a younger heart. This extra blood volume allows the older heart to pump out just about as much blood with each beat as a younger, smaller heart, even though it has a lower ejection fraction. This represents the Frank-Starling mechanism working at its finest. However during vigorous exercise the older heart is still pumping less blood overall because it can’t beat as fast as a young heart.

| |

Changes in the aging heart result in

reduced cardiac output during exertion. However, regular aerobic exercise, such as swimming or water aerobics, can improve fitness and diminish the effects of these age-related changes. |

While this adaptation certainly helps the heart meet the immediate needs of the exercising older body, it does so at a cost. As the older heart dilates between beats, wall tension and pressure within its cavities rises. This increases load on the heart and forces it to work harder. In the long run, persistently elevated pressure promotes thickening and stiffening of the ventricular walls. As a result, the ventricles don’t fully relax between beats, and this—combined with a greater filling volume—causes end diastolic left ventricular pressure to increase. When this happens the left atrial pressure increases and this pressure increase is transmitted to the lungs. As pressure rises, oxygenated blood has trouble getting from your lungs into the left side of your heart so it can be pumped out to the body. One outward sign of this scenario within the lungs is that you begin to feel short of breath while exerting yourself. How much exercise you can do before you experience this symptom depends, in part, on how much of the left ventricle’s pumping capacity has been eroded. Regular aerobic exercise can help diminish the impact of many of these age-related changes.

|

When the Brain Talks to the Heart: Does Age Matter?

The brain talks to the heart through the nervous system, using the language of biochemistry. Substances called neurotransmitters travel from nerve cell to heart cell, deliver the brain’s messages by binding with special receptors on the membranes of heart cells, and set off a chain of molecular events that ends with a faster beating heart, stronger contractions, and faster relaxation between beats. Or, depending on what neurotransmitter is used, the brain can tell the heart to reverse all of these effects.

This heart-brain dialogue occurs through the autonomic nervous system without you having to think about it. This system automatically regulates all of the body’s processes like breathing or digestion that don’t require conscious control. But as we age, some of these lines of communication begin to fray, and the heart doesn’t respond to the brain’s messages as promptly or as well as it once did.

| | When the Brain Talks to the Heart

Click here for

larger view |

For years, scientists were puzzled by this phenomenon, but they may be getting closer to understanding how and why these messages get muffled. In particular, investigators are looking at the sympathetic nervous system, the part of the autonomic nervous system that signals the heart to speed up. This subsystem helps regulate the heart beat through a series of signals passed from neurotransmitters to receptors on the membranes of heart cells. One of these important signaling cascades starts when neurotransmitters, such as catecholamines, bind to special protein molecules, called beta adrenergic receptors, on the heart cell membrane. Once activated by a neurotransmitter, these beta adrenergic receptors set off a chain of molecular events that allows more calcium to enter heart cells. Increased calcium within these cells can lead to a stronger and more rapid heart beat.

But as we get older, something goes awry in this signaling cascade. As a result, the older heart can’t respond to these neurotransmitters, so it doesn’t react to stress as well as a younger heart. During exercise, for instance, an older heart is less able than a younger heart to increase its heart rate, augment its contraction strength or boost its cardiac output to meet the needs of the body.

At first, researchers suspected that the diminished supply of catecholamines and other neurotransmitters might be the problem. To test this theory, NIA investigators infused catecholamines into the blood streams of older and younger volunteers to simulate the effects of exercise. As expected, the heart rates of the young men increased. But the older men’s rates increased less, even though they received the same supply of catecholamines. So the problem wasn’t supply.

Could the problem then be somewhere in the aging cardiovascular system’s response to catecholamines? Studies show that this is probably the case. There is a drug called propranolol which blocks the body’s response to catecholamines by blocking the beta adrenergic receptors on heart and blood vessel cells. Propranolol and aging have the same effects, according to a number of studies. Older hearts and blood vessels, apparently, have blocked some of these beta adrenergic receptors.

Investigators soon found that with age the number of beta adrenergic receptors on heart cells did diminish. But this reduction was only modest. Instead, studies now suggest that something else about these receptors changes with age: the number of them that are capable of binding with catecholamines, i.e., those in a “high affinity state,” seems to decline with age.

The reason for the reduced response could lie anywhere in the cascade of events in heart muscle cells that occurs after catecholamine binds to the receptor. Scientists are finding a host of possible cellular mechanisms that might explain the reduced response. They hope once these mechanisms are better understood, they will be able to find a way to mend the link or prevent it from disrupting messages in the first place. Eventually such findings could lead to new ways to prevent heart failure.

Click here for larger view

Click here for larger view